Bonfire Night is a prominent date in the British calendar and whilst it sadly doesn't warrant a day off work, it is at least a significant night for many families and communities who gather together and set fire to things. Yet despite the common knowledge we have about November 5th, it is surprising that the setting for those fateful events is almost entirely anonymous.

Bonfire Night is a prominent date in the British calendar and whilst it sadly doesn't warrant a day off work, it is at least a significant night for many families and communities who gather together and set fire to things. Yet despite the common knowledge we have about November 5th, it is surprising that the setting for those fateful events is almost entirely anonymous.To unwitting eyes, the current Houses of Parliament look suitably ancient and an appropriate setting for a 17th century espionage drama. But despite its Gothic styling, the modern parliament building wasn't fully completed until just 140 years ago. The original Westminster was not one single palatial building as it stands today, but a mis-matched collection of structures from different centuries, repeatedly altered and re-purposed many times by different kings. Compared to what stands in its place today, the building which Guy Fawkes attempted to destroy was surprisingly small and unremarkable, and all traces of it are now lost. What do know about it, and what did it look like?

We begin our search behind the MI5 Security Service building in central London, where we find Thorney Street. This street name is the last clue surviving to the course of a waterway which joined the River Thames here. The River Tyburn entered the Thames via rivulets which formed a small island, and this patch of dry land was named Thorney Island.

Upon this empty island, some distance from the walled capital of England, it was perhaps as early as 1016 that a royal residence was first sited, possibly by Cnut the Great.

Around 1045 Edward the Confessor constructed a royal palace along with a magnificent Abbey. The location of his new Minster, situated west of the City of London soon resulted in Thorney Island and its buildings being dubbed the "West Minster" area.

The earliest depiction of Westminster Palace comes from the Bayeux Tapestry (of which a modern copy is shown above) and it was William the Conqueror's son William Rufus who began building a new Palace when he came to the throne in 1087. It was his hope that the new palace would match the splendour of the adjacent Abbey, but his dream was never fully realised. Remarkably it is from this phase of construction that the great hall dates which still stands today, known as Westminster Hall.

In the 12th century, a second hall was built to the south and during the reign of King Henry III in the 13th century, several new structures were built and modifications were made. One such change regarded a hall called the Queen's Chamber to the south.

In the 12th century, a second hall was built to the south and during the reign of King Henry III in the 13th century, several new structures were built and modifications were made. One such change regarded a hall called the Queen's Chamber to the south.This Queen's Chamber was a modest stone construction built up on the first floor, and aligned north-south. According to sources such as William Capon, the ground floor of this building was the site of Royal Kitchens built by Edward the Confessor.

This Braun map of London from 1572 (right) gives us a glimpse of the old Palace on the banks of the Thames and we can start to get a feel for the layout of this site. However, the accuracy of this map is less than perfect as there aren't enough buildings depicted for the number that would have been there.

Parliament (and its earlier incarnation) had been meeting in Westminster Hall since the 1200s, but after fire destroyed many buildings in 1512, the purpose of the Westminster complex shifted from being a royal residence to primarily being the home of parliament.

The House of Lords settled into the hall that had been called the Queen's Chamber, already four hundred years old at this point. Beneath this hall, the large space on the ground floor (formerly the royal kitchens) became privately owned. On the left is an engraving from 1799 by G Dale showing this room, said to be 77 feet long, 24 feet and 4 inches wide, and with a roof 10 feet high. Often said to be a basement or cellar it was termed an "undercroft" and not situated beneath ground, but was accessible directly from the street level.

Within the modest stone hall above, the King and nobles were scheduled to meet at the end of the year of 1605. The ramshackle arrangement of buildings at Westminster meant that merchants of all kinds lived and worked in the shops and taverns, and there was no restricted access to important nearby buildings. Thus, beneath the first floor of the House of Lords, the undercroft owned by John Whynniard was leased out to the gunpowder plotters.

Within the modest stone hall above, the King and nobles were scheduled to meet at the end of the year of 1605. The ramshackle arrangement of buildings at Westminster meant that merchants of all kinds lived and worked in the shops and taverns, and there was no restricted access to important nearby buildings. Thus, beneath the first floor of the House of Lords, the undercroft owned by John Whynniard was leased out to the gunpowder plotters.John Rocque's map of 1746 (pictured right) provides a more accurate ground plan of the main buildings in question. Westminster Hall dominates the area to the north, and the House of Commons is labelled occupying St. Stephen's Chapel. The House of Lords to the south appears extremely small by comparison to everything around it.

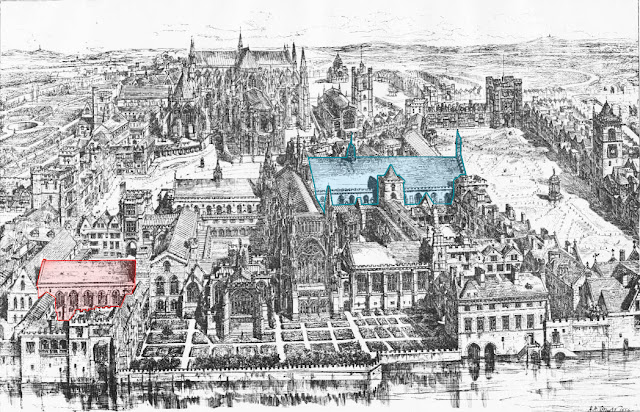

This image on the left gives an accurate 3D sketch of the layout of the buildings. Our view is looking north, with the Thames to the east.

This image on the left gives an accurate 3D sketch of the layout of the buildings. Our view is looking north, with the Thames to the east.Not fully depicted are the lesser structures of what had become a heavily developed area. As well as the prestigious buildings of state, a warren of additional wooden houses and shops would have butted up against them and formed narrow streets around the place. On this illustration the small House of Lords is picked out in red, behind the Queen's Chapel. Westminster Abbey dominates the area just to the west.

Despite its significance, there is a distinct lack of imagery of the old Westminster and the artwork that does exist tends to be extremely limited in what is shows. One depiction comes from a Dutch map started by Wencesclas Hollar some time after 1688. The map itself is fairly useless for the study of the area, however it is adorned with illustrations, one of which is below.

The view depicted is facing west with our back to the River Thames. On the left of the frame and looking like a church is the north entrance to the great Westminster Hall.

Just peeking over the wall is the blue-grey roof of Westminster Abbey which runs at right-angles to the parliament buildings.

But once again our place of interest - Guy Fawkes' terrorism target - is not shown. Westminster Hall was impressive enough to warrant an illustration and yet the building with the greater political importance was tucked away around the back and not pictured.

Another piece of work by Wenceslaus Hollar is this engraving (left) which dates from 1647, but just like the other representations of the time, Westminster Hall is given centre stage, with the Abbey behind and St Stephen's Chapel on the left, home to the House of Commons.

With all near-contemporary illustrations of the area showing only the big, impressive buildings, what do we actually know of the hidden setting for the treasonous plot?

Could it be that the exterior was a actually a diminutive masterpiece...?

Could it be that the exterior was a actually a diminutive masterpiece...?We finally arrive at what is probably our best, clear view of our terrorists' target building. Unfortunately it dates from two centuries too late, but this 1807 image reveals the (then former) House of Lords in its later life to be little more than a dishevelled old stone hall overlooking an untidy yard. It was hardly a venue befitting the seat of power for the entire country.

This beautiful drawing below by H J Brewer dates from 1884 and is a suggested reconstruction of the Old Palace at the time of Henry VIII. The main Westminster Hall is picked out in blue near the centre whilst The House of Lords is in red. Note the different number of windows and the longer structure compared to the 1807 interpretation - showing how little confirmed information there was about it.

This artwork gives a powerful indication of just how much collateral damage would have been caused to the surrounding site if the gunpowder had been ignited. The House of Lords was connected to buildings at both its north and south end, with the Painted Chamber and Court of Requests just a few yards away.

But, as history records, the plot was foiled. The king and the Parliament buildings were saved. For a while at least...

Given its ageing state and jumbled location, it is perhaps not surprising that this medieval House of Lords chamber was demolished about a century after the Gunpowder Plot. According to Thornbury the hall was destroyed "and some mean brick edifices were erected in their stead". Shortly after this, fire tragically broke out which destroyed most of the remaining ancient buildings on the site. This painting depicts the aftermath of the 1834 fire, with the ruined St Stephen's Chapel on the right, and the "brick edifices" on the left where once the old House of Lords had stood.

The disaster resulted in the rebuilding work which would see the creation of a brand new Palace of Westminster, and the foundation stone of the modern building was laid in 1840.

The image on the left shows an overlay of the 17th century ground plan in yellow on top of the modern site. The House of Lords is highlighted in red.

The image on the left shows an overlay of the 17th century ground plan in yellow on top of the modern site. The House of Lords is highlighted in red.Westminster Hall and the adjoining courtyard were the only elements which were preserved after the fire, and remain relatively unchanged to this day. The east side of new Gothic palace extends further forwards to meet the bank of the river Thames on reclaimed land.

So, given the historic significance of the old palace buildings, why do we know so little of them, and why do they make so little impact on our telling of the Guy Fawkes story?

The "happy ending" of the Gunpowder story is the saving of lives and the preservation of our political system. The building which was also triumphantly saved in the process was later voluntarily destroyed, thus eliminating any thoughts about it being a victory for architectural preservation.

Images of the early Westminster complex are rare and not exceptionally inspiring. This Samuel Scott painting from 1746 (below) is typical of the view; dominated by the Abbey, and Westminster Hall (behind the trees). The ancient stone House of Lords is lost amongst the jumble of nondescript buildings and when singled out it is quite underwhelming. It was steeped in history, but its time had passed and its usefulness had come to an end.

The real tragedy about the old Palace was that fire destroyed the beautiful St Stephen's Chapel and other buildings surrounding it. If there is any architectural "happy ending" to be taken from this tale, it is that the amount of gunpowder the plotters used might have damaged the nearby Westminster Abbey and Westminster Hall. Stone and flaming debris would have been propelled in all directions at hundreds of miles per hour, along with a devastating shockwave which would have ripped through the narrow streets. Fires would have burned and many lives would have been lost, not just those in the Parliament.

If the Gunpowder Plot had succeeded we might have been deprived the full splendour today of two of our oldest and greatest buildings in London, as well as having the legacy of the devastating consequences of the assassinations and mass-murder.

Fantastic :-)

ReplyDeleteDear Gav,

ReplyDeleteGood article - but just to clear up some misconceptions I thought I'd comment. I was Deputy Curator for the Parliamentary works of art collection when we celebrated the 400th anniversary of the Plot in 2005 and contributed to two programmes - Darlow Smithson's Gunpowder Plot, Exploding the Legend and BBC Timewatch Gunpowder Plot (both on YouTube). For both we 'recreated' the old House of Lords - for the Darlow Smithson production in concrete wood and scaffold on the original proportions to see what the plot would have done if successful and for the BBC we reconstructed a CGI model based on all the known architectural drawings of the old palace (your London 1605 is a still from the panorama of it) which unfortunately is no longer online though bits of it are on Youtube (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Kas_HOy3fA&feature=relmfu).

The old palace of Westminster was a particular area of study of mine. There's actually quite a lot of good images of the old House of Lords and your article gives a lot of them - one you don't mention is J T Smith who undertook and published a book on the Antiquities of Westminster in which he collected an reproduced lots of earlier drawings of old parts of Westminster including the Parliament buildings in 1807 and wrote descriptions (your view of the old House of Lords of that date is from it). A good source of images are two less well known online resources - the Parliamentary Art Collection (search on 'old palace' or 'view of westminter' or particular buildings 'cellar' 'painted chamber' and the Guildhall Art gallery's prints collection available via Collage (see links below). Your main mistake however is the Thornbury quote - he's describing the new King's Staircase and Royal Gallery built by Sir John Soane as part of an improvement scheme in 1822 the 'Scala Regia' was an impressive neo-classical staircase which was built from the new King's Entrance and led to the Old House of Lords. Most of it survived the fire of 1834 and continued to be used until Sir Charles Barry's New Palace of Westminster was nearing completion - it was then demolished in 1851 - there's a view by George Scharfe of the Victoria Tower half constructed and Soane's buildings still standing. If you or anyone else wants to read further get hold of The Houses of Parliament ed by Jacqueline and Christine Rider (Jacqui was my predecessor) which has a good chapter on the old Palace!

Anyway, hope you don't mind some further information - it is a particularly fascinating lost building which at some point I'd like to write about in more depth - maybe when I retire! Simon Carter (Twitter/Blog MrAvoncroft)

http://www.parliament.uk/about/art-in-parliament/

http://collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk/collage/app?service=page/Introduction

Interesting background story to the Gunpowder Plot and I love all the illustrations you've found.

ReplyDeleteI thoroughly enjoyed this post and appreciate the research you put into it. Looking forward to your posts in the future.

ReplyDeleteVery excellent research! It was a delight to read!

ReplyDeleteKREDITNO PODUZEĆE ZA FINANCIJSKO PLANIRANJE TREBATE LI FINANCIJSKU POMOĆ? JESTE LI U FINANCIJSKOJ KRIZI ILI SU VAM POTREBNA SREDSTVA ZA POKRETANJE VLASTITOG POSLA? TREBATE LI SREDSTVA KAKO BISTE PODMIRILI DUG ILI ISPLATILI RAČUNE ILI POKRENULI DOBAR BIZNIS? IMATE LI NIZAK KREDITNI REZULTAT I TEŠKO VAM JE DOBITI KAPITALNE USLUGE OD LOKALNIH BANAKA I DRUGIH FINANCIJSKIH INSTITUTA? EVO VAŠE ŠANSE DA DOBIJETE FINANCIJSKE USLUGE OD NAŠE TVRTKE. NUDIMO SLJEDEĆE FINANCIJE POJEDINCIMA- *KOMERCIJALNE FINANCIJE *OSOBNE FINANCIJE *POSLOVNE FINANCIJE *POSLOVNE FINANCIJE *POSLOVNE FINANCIJE I MNOGO VIŠE: ZA VIŠE DETALJA. KONTAKTIRAJTE ME PUTEM. E-MAIL Pošaljite nam e-poštu: smartloanfunds@gmail.com Svi tražitelji gotovine trebali bi nas kontaktirati Whats App +385915608706

ReplyDelete